Marlin Barton Talks Novellas

Who better to discuss the form than an author who has just published his last novella excerpt? Read Part 3 of "Playing War" here

What’s in a Name? A Few Thoughts on the Novella / By Marlin Barton

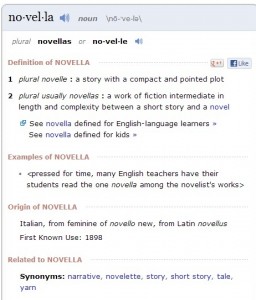

Though Katherine Anne Porter wrote three of them, “Old Mortality,” “Noon Wine,” and “Pale Horse, Pale Rider,” she hated the term. She preferred the phrase “long story” to “novella.” I’m not sure why. There’s a kind of beauty in the sound of the word itself, I think. Maybe that’s one reason I prefer it. Sometimes one hears the word “novelette,” which sounds downright silly to my ears, and as the writer Lou Mathews pointed out in remarks for Failbetter upon the publication of his novella “The Irish Sextet,” it sounds as if it could be the name of a girl-group from the early ’60s, The Novellettes.

So what do we call these things, and how do we define them? We can agree they’re longer than short stories and shorter than novels. But how much does that really tell us? If you look up novella contests on-line, you’ll find guidelines that vary from 40 to 150 pages and word lengths from 10,000 to 42,000 and more. There are simply no easy answers, and I’d suggest that is part of their appeal for writers. They have a kind of in-betweenness to them, an elasticity. They live in that gray area, and isn’t that where fiction writers live, too, and not in the black-and-white world of easy answers for life’s questions, moral, artistic, or otherwise?

Since their word length, and even what we want to call them, can be difficult to pin down, maybe there’s something about their content, or even intent, that can help us decide what they are. I’ll offer a few thoughts, my two cents, which may be about what these remarks are worth since all writers have to decide for themselves what they’re creating and how they want to define their creations. When I began to envision my novella (there, I’ve said the word), “Playing War,” which Failbetter has been kind enough to publish (and which is probably on the short side at 21,000 words and 68 manuscript pages), I knew it would be longer than my typical twenty-page story, and it seemed that it might have a more complex plot and maybe even a greater emotional, and moral, complexity than what I normally attempt in a short story—if I could achieve what I intended. Of course, I also hoped that I didn’t know already everything that would happen in the story I wanted to tell. I wanted to explore the characters and their situation and see what I might discover. I thought it might run 100 manuscript pages or so. Turned out a bit shorter, but I do think it has a more complex plot than any story I’ve written, perhaps more than most “typical” stories, and I hope maybe even a greater emotional and moral complexity than a typical story, or at least for one of my stories. Of course, many writers and readers will say now that even a short, short story (or sudden fiction, or flash fiction—what do we call these things?) can have great moral and emotional complexity. Layers of complexity do not belong only to the novella. So here we are again, trying to define something that can’t be defined. I say we simply celebrate its in-betweenness, realize that when we can’t easily categorize a piece of fiction, we may just have a novella on, or in, our hands. And while novellas, due to their length, can be as difficult to place in print journals as they are to define, the good news is that with the now widespread availability of on-line literary journals likeFailbetter, print space is no longer an issue, which opens up all kinds of avenues for a literary form that encompasses writers from Conrad to Porter to contemporaries such as Michael Knight and Cary Holladay, and maybe to you too, if you might be so inclined to find your way into such a slippery form.