Three ways of looking at a mountain

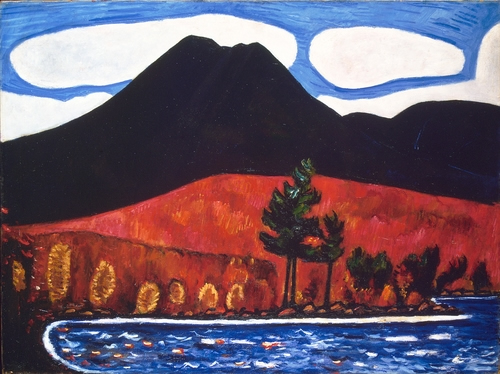

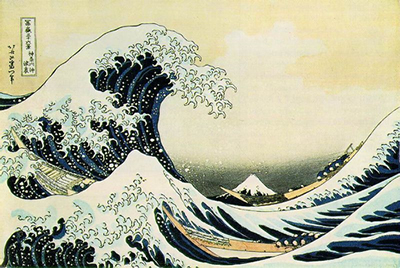

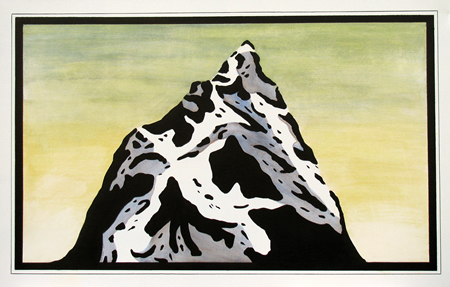

When William Auten sent us images of his new paintings - the Mountain series, up this week - I was struck by the sense that they're as arresting, and in a similar fashion, as the great "mountain" works by Katsushika Hokusai and Marsden Hartley, and yet they're in some way quite different. But at first I couldn't figure out what the difference is. In each of these works, the artist abstracts his mountain, flattening out details in favor of largely unmodulated color fields, and making the thing seem a flat mass with no relief. Hartley and Auten seem to go further in this, as Hokusai's neat, even lines and verisimilitudinous contours can make us, on first glance, assume that his mountains are more "realistic." But they, too, are mostly assemblages of Colorform-ish shapes; even in those in which those shapes blend into one another, as gradients, the mountains' volumes are rendered as two-dimensional, with the distinct, even edge lines making clear that the plane of the drawing is meant to be taken as that of the scene as well.

So what's different about Auten's works? I had to look at them for a while to figure this one out. Finally, I realized that he goes one big step further than Hartley and Hokusai, in turning his mountains into abstractions. Note that in these works, there are no other elements to give us a sense of the mountain's scale - which, after all, is every mountain's key feature. Auten vignettes his mountains too, to ensure that we encounter them as things in themselves - sculptural shapes more than natural objects, with the craggy edges and white fields seeming less nature's work than his, and only after reflection, in light of the title, do you see "peaks" and "snow." Note too in this context the dark, thick, Lichtensteinian lines with which he outlines each mountain's every feature, as well as the mountains themselves. This serves not just to emphasize their mass, but also, after a moment of staring at any of these works, convinces you that the mountain's features don't necessarily adhere together to make a single object, but rather are a set of distinct fields, each bearing no more relation to the others than to the "sky" fields toward the tops of the images.

Does this move toward abstraction, and aestheticization, make Auten's works in some way more interesting or successful than Hartley's or Hokusai's? Not necessarily - those works deserve the status of classics, each bold and new, visually striking and rich in color, imagery static yet with a restrained power that makes them also dynamic. Not to speak of both artists' powerful sense, and use, of color. But Auten's works are beautiful and arresting as well, and all the more so because in depicting his mountain, he doesn't settle for giving us a mountain, and nothing more.