Don’t Breathe. Now Breathe

I’m a radiology tech in the breast center. I do mammograms, maybe fifteen a day. We start early here — 6:30 — for the working women who want to stop by on their way to the office and check it off the list for another year. You might think it’s like going to the dentist, a minor unpleasantness. But it’s not. Because beneath the routine is that tiny worry, the one you push away and push away, but then there it is again.

Almost every woman comes into my imaging room a little bit scared, thinking about her aunt or her friend who died, or remembering the pictures she’s seen of a scarred chest where a breast used to be. Maybe she’s felt a lump, a hard ball of tissue deep inside that doesn’t belong. She touches it in the shower, and in bed at night. She feels for it when she’s in the ladies room at work.

So no, it’s not like the dentist at all.

Chance is a funny thing. A woman has one-in-eight odds of getting breast cancer in her life. If you’re given one-in-eight odds of winning something, you might say it’s a long shot. But a one-in-eight chance of cancer can seem like a certainty when you’ve felt a lump or noticed a weeping nipple. You go for the mammogram and maybe the technician doesn’t smile at you, and you take it as a sign. Or maybe she takes too many pictures or goes across the hall to speak to the radiologist, leaving you alone in the chilly room. And that night you spend hours wandering through your apartment or lying next to your sleeping husband, so sure of a tumor that you can feel it growing beneath your skin, the cancer cells spilling hot, like lava, until there’s nothing left but scorched tissue and the coiled snake of malignancy.

Still, I like my job, and I like getting in early. When I walk into the hospital, hear the hum of machinery, see people chatting in the cafeteria and smell the sharp disinfectant soap we use, I feel like I’m part of the world. Like I do something that matters.

My first appointment of the morning: Elena Ortiz, age 40, no history with us, so maybe a first-timer. I key in her information, then go to the mammography waiting room — pale pink walls, subdued grey and pink plaid carpet, framed prints of flowers on the walls. The space is supposed to be calming, like a living room, but the boxes of Kleenex are the giveaway.

“Ms. Ortiz?” I look into the middle of the room, neutral. Don’t assume the stocky, black-haired woman — the one drawing something in a notebook — is Ms. Ortiz. The dark-haired woman stands. She closes her notebook and caps her felt tip pen, her face serious.

I like imaging Hispanic patients. Their chances of getting breast cancer are measurably lower than white women, and their breasts tend to be large and easy to handle. This will be an in and out, see you next year.

“Hi, I’m Beth. I’ll be your technician today. We’ll make this as quick as possible.” I smile in a professional way. I keep my voice soft and calm, but detached. That’s to help her get through it. After a few minutes, Ms. Ortiz comes out of the dressing room, her top half wrapped in a paper gown. We start with the left breast. I position her close to the machine, closer than she wants to be. She steps back and I have to gently push her forward again, reposition her. I undrape the breast and show her how to hold the metal bars with her hands so she can stand motionless for the image. Then I take her breast in my hands.

A breast is vital and warm, like a small animal. Sometimes the flesh of it is thick and the tissue beneath it muscular. Sometimes the breast is so small that I can barely find enough of it to place on the imaging paddle. Ms. Ortiz has a heavy breast, soft and elastic, the dark skin of it striated with white stretch marks, the nipple large and dark.

My job is to compress the tissue so I can get a good image. I stretch it and tug it and rest it against the lower paddle. Then I press another paddle hard on top of it, squeezing and flattening. This hurts, especially if the breast is big. Sometimes a woman will gasp and then laugh a little, embarrassed by the pain. Sometimes tears come to her eyes. But most are soldiers, marching through as stoically as they can.

Once Ms. Ortiz is positioned correctly, I go behind the glass to the control room. I turn on the microphone and say, “Hold still. Don’t breathe… don’t breathe… now breathe.”

Before a woman leaves, I’m supposed to give her one of our pink ballpoint pens. “Memorial Breast Center,” it reads. “Keeping you in the pink.” Most women say thanks, but others hesitate, seeing this exchange as an opening. “Did everything look OK?” they’ll ask, or, “Just tell me. How bad is it?”

That’s when I have to lie. “Oh, hon,” I say, “I wish I knew. All I do is take the pictures. Your doctor will be in touch.”

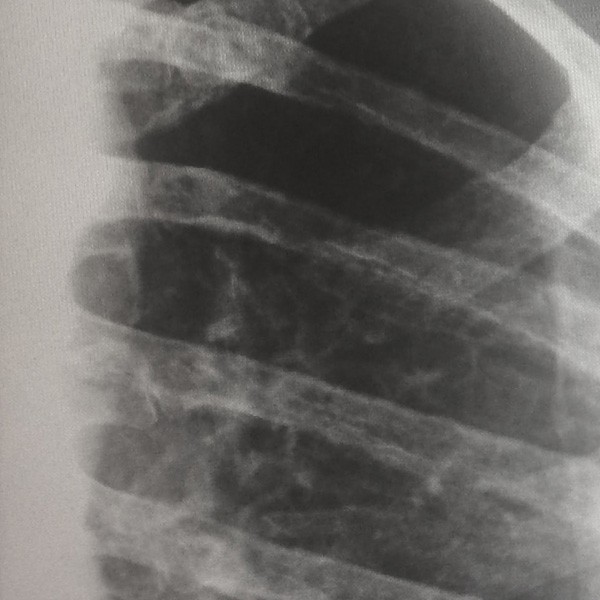

But I do know. I look deep into their breasts, and I see everything: ductal cancer, lobular, mucinous, mixed tumors, some so massive they distort the breast. I see the purple rashes of inflammatory cancer. The leaking nipples. Sores, sometimes.

Sometimes there’s just the smallest white spot, barely there, but there. I see it on Mrs. Ortiz’s left breast, near the areola.

After work, I swim. In the locker room, I shed the day and pull on a swimsuit tight as a second skin. I move through the cool water like a machine, thinking of nothing, counting my laps, feeling my arms slip through the liquid. I breathe, pull and kick.

When I had just one breast, there was an imbalance to my strokes, no matter how subtle, an exaggerated roll to one side that slowed my forward motion, like walking with a limp. But after the second breast had been removed, the balance was restored. Now I slip through the water like a fish, unimpeded.

Breathe, pull, kick, flip, push from the wall. I watch the green tiles move beneath me, watch the bubbles, watch the blue water. My goal is to get so tired that my arms and legs feel like dead weight, so tired that I can sleep. Usually it works.

The important thing is, I made it through, two times. Most women do: six months or so of a life reduced to pain, nausea, the weekly trudge to radiation or chemo. And of course, there’s also the revelation: the first time a woman’s husband or lover sees that scarred and empty place and she watches his face for a sign of what the future will bring.

Maybe Ms. Ortiz’s husband will look and then look past it. Mine could not.

Before the surgery, after the surgery, my husband was so tender. While I was healing, I kept covered. I didn’t want him to look, didn’t want him to feel sorry for me. The drains, swelling and rough red scars were too much for anyone. My husband didn’t ask to see the damage. I didn’t blame him. I didn’t like looking at it either.

At last I healed. I wasn’t a candidate for implants, so I ordered breast forms (two, right side only) and a few mastectomy bras. I even got a black one with lace. That turned out to be a waste of money.

I wore it one day when I was feeling good. My hair was growing back in and I’d colored it a pretty blonde. It looked cute on me, my little blonde pixie cut. I’d lost the jaundice. I looked pink and healthy. My husband was in the kitchen unloading the dishwasher. I went up and wrapped my arms around him and kissed his neck. He turned to me, the skin on his neck flushed that way it always did when I kissed him.

“Really?” he said. “It’s OK?”

We were both so ready that we rushed upstairs, taking our clothes off as we went. I felt like I was 22 again, wild and in love. I unhooked my bra and threw it on the floor, and that’s when my husband saw the scar.

“Oh no,” he said, and his voice was so pained that I grabbed a pillow and held it to my chest.

“I’m sorry,” he said. “I didn’t realize…”

“No, no, it’s my fault. I should have shown it to you before. I didn’t think…”

We apologized to each other a few more times, carefully, like polite strangers who’ve knocked into each other on the subway.

“It’s OK,” he finally said, and I dropped the pillow. He tried to look, but then turned his eyes away — first from the scar, and then from me.

“Look at it,” I wanted to say. But I couldn’t.

“I’m sorry,” I said again, and I put my lacy bra back on.

I had to get out of the room. I left him sitting on the bed.

We tried again a few days later, kissing on the sofa, his hand outside the bra, on my good breast. Then our hands on each other, teasing and playing the way we used to, and the slow removal of clothes, the black lace bra coming off last, both of us ready. And then only one of us ready. And then, very quickly, neither of us.

We tried again, and this time I kept the bra on, but he wasn’t able.

“I’m afraid to hurt you,” he said, but it wasn’t that. The body only likes what it likes, and it always tells the truth. I repulsed him. That thing between us — the hot, wet, wanton thing we’d loved and counted on all those years — that thing was dead. We mourned it with tears and silence.

I ordered some long nightgowns and started dressing and undressing in the bathroom. Later, when I could no longer stand to see his healthy, unscarred body above a flaccid penis, I moved into our daughter’s old bedroom.

The death of a marriage can be quick, like a heart attack. You discover an affair you can’t forgive. Or it can be a slow eating away. At first we were affectionate roommates, joking, sharing kitchen chores, watching TV together. We even took a six-week course of ballroom dancing, but our waltzes were awkward and strange.

When we went into our separate rooms at night, my husband looked troubled and ashamed. I felt sorry for him, but I felt worse for myself.

I told myself that plenty of couples our age lose interest and give up sex. I told myself that we could still make a good life together, that our relationship was so much deeper than just sex. We had a daughter together. A long and happy history. We were a family.

But that wasn’t true. Because deep inside, this dark fact feasted on me: there was something about my very being that repelled my husband. His body couldn’t lie. And there was no way to ignore the truth or pretend it didn’t exist.

Knowing this, I discovered that I couldn’t meet his eye. I became like some small, unwanted creature that scurries along close to the walls, trying to be invisible. I spent more and more time in our daughter’s bedroom. I read and watched TV. Then I got mad. Mad that his disgust was so visible. Mad that he couldn’t force himself to overcome it. Mad that this awful thing was happening to me. I got a vibrator and didn’t care if he heard the buzzing.

I was the one who finally had to end it. I was certain that I felt lonelier and angrier with him in the house than I would if I were alone. He left, crying, and his crying left me cold. After a few months, it was a relief to both of us, a blessed letting go. I bought a new bed and soft cotton sheets, soft down pillows, and I painted my bedroom pale yellow. After holding my breath for so long, it felt good to exhale.

Our daughter is angry that I — as she says — threw her father out. She’s 24 and righteous. I can’t tell her the truth and my husband won’t.

When the second breast had to go, my husband visited me once in the hospital and brought a bouquet of sad red roses that clearly came from the hospital gift shop. They wilted after a single day.

Some men stay. Most men, probably. They learn to accept it. Maybe they congratulate themselves on their acceptance. Or maybe it doesn’t bother them at all. There must be some men like that.

Some of them ask their women to get implants, maybe a little bigger and firmer than what they had before. They suggest nipple tattoos. Most of the time, that’s what the women want too, until they find out that getting implants hurts, too. But they get them anyhow, go through the skin stretching and the implant surgery and sometimes a second or third surgery to get rid of lumps and excess skin. They want to get back to normal and forget everything. But you never forget.

*

A few days later, Ms. Ortiz is back for reimaging. This time, she brings along a girl of 14 or 15, already carrying her own set of heavy breasts. “Hi, there, Ms. Ortiz,” I say. “Is this your daughter?”

Ms. Ortiz gives me a shrewd and frightened look, then nods briefly. I’m the torturer and messenger; nothing good can come from me.

Ms. Ortiz is trembling. She thinks we’re going to find something worse than what we’ve found already. She thinks she’s going to die. As we walk down the shiny linoleum hallway, she drops her notebook. I bend to pick it up for her. A page has fallen open to a blue pencil sketch of a swallow. It’s an accomplished drawing; the feathers are detailed and the shading expert. The bird soars upward at such an angle and with such determination that it looks as though it will leave the atmosphere altogether.

“I like your bird,” I say.

She smiles briefly. “The swallow,” she says. “This bird, she brings solace.”

I hand the notebook back to her and she tucks it in her purse. We go into the imaging room.

“I’m so cold,” she says. Her face is pale and dry. I want to tell her that everything will be fine. I want to wrap her in my arms and hum to her. But I can’t. Because no matter what happens, everything won’t be fine. Things will be lost. Instead, I do what I can do. While she changes into her gown, I go to the blanket warmer. When I come back to the imaging room, she is standing dutifully by the mammography machine, still shaking. I drape a warm blanket over her shoulders and lead her to a chair.

“We have time,” I say. “Sit for a minute before we get started. Warm yourself up.” I put a second blanket over her legs.

My friend Maura thinks I should get another job. She works in the nursery, a happy place. “Move over to X-ray. Take pictures of hunky young guys who’ve broken their legs playing football,” she says, “toddlers who’ve shoved beans up their nose. Anything but this.”

Maura assumes I’m hurting myself. She thinks my job depresses me. And maybe it does. But this — this invasion — needs a witness. Ms. Ortiz needs a witness. Someone who’s not afraid to look.

After a few minutes under the warm blankets, Ms. Ortiz nods twice to herself. She’s made a decision. She stands up, carefully folds the blankets and places them in the chair.

“Thank you,” she says, and she stands up a little straighter. She’s ready to go into battle. She steps to the imaging machine and takes a deep breath. Again I take her heavy breast in my hand and squeeze it between the plates. Again I repeat the litany: Don’t breathe, don’t breathe, now breathe.

When it’s over, when she’s dressed again, I walk with her to the waiting room. I never do this, but I want to return her to her daughter. The girl is texting on her pink phone, but when she sees her mother, she stands and takes her hand. They seem so alone in the world, the two of them standing there, and I wonder whether there is a Mr. Ortiz. I wonder whether the girl has it in her to care for her mother in the coming months.

Once the doctors find something, things move quickly. You’re caught up in a system that everybody but you understands. People speak to you, but there’s a buzzing of bees that confuses you and makes you stumble as you go from office to office: oncologist, radiologist, surgical nurse.

“Do you understand?” they say. “Do you have questions?” You nod. Yes, I understand. But you don’t. Because until the surgery, you’re innocent. You don’t understand pain and the endless humiliations your body has in store for you: cracked and chapped lips that won’t go away; the exposed and tender scalp; a stomach that won’t stop heaving, even when there’s nothing in it; drains and Foley catheters, and of course the wounds where a lovely breast once was.

Ms. Ortiz weighs on me. It was her steadfast look. The careful way she folded the blankets. The lack of a wedding ring. And of course her extravagant swallow. I find out she’s scheduled for surgery. A full mastectomy, plus removal of the lymph glands under the armpit. It was worse than it appeared on the first images. I tell myself to stay away, but I know I won’t. I keep picturing the mother and daughter standing in front of me, so somber. The day after the surgery, I stop at the gift shop. The roses still look sad, but the small bunch of pink carnations looks OK. It’s late afternoon. Mrs. Ortiz will probably be awake. I walk down the hallway, so quiet in the early afternoon, the warm, damp smell of lunch still in the air, the televisions murmuring.

Ms. Ortiz is alone, dozing, the TV on mute. When she hears me tap on the door, her eyes open, and it takes her a moment to recognize me.

“You came?”

I put the flowers on her tray table.

“You doing OK?”

Ms. Ortiz shrugs. She’s small in the white bed.

Suddenly I don’t know what to say. Coming here was a mistake. I start thinking of reasons to leave. Then she extends her hand to me. It’s icy.

“You’re freezing.” I smile again. “That seems to be a problem with you. Do you want a warm blanket?”

She shakes her head. Then she turns away.

“You’re not going to die,” I say.

She turns back to me, and her face flashes red. “How do you know that? How do you know? You’re no doctor. You just take the pictures; you said so yourself. ‘Don’t breathe. Now breathe.’ That’s all.”

I stare at her for a minute, remembering my own fear and rage, sharp and humiliating. Then I pull the curtains closed around the bed and step inside the cocoon. Ms. Ortiz’s anger turns briefly to alarm as I begin to pull up my uniform top and t-shirt. Then she sees the scars. But mostly she sees what’s no longer there: breasts, nipples, muscle beneath the armpits.

She looks for what seems like a long time and then says, “OK.”

I cover myself.

“Where’s your daughter?”

“In the cafeteria with my mother. They’ll be back.”

I start to pull the curtains open, but Ms. Ortiz says, “Wait.” She pats the bed. I go and sit next to her.

“Show me again.”

I pull up the shirts. Ms. Ortiz leans forward and takes a bright blue felt tip pen from the tray table and motions for me to lean in close, so close I can feel her breath on my skin. Then, with infinite care, she begins to draw a swallow on my scarred and naked chest.